An ode to the front-engined Top Fueler, and to the family ties that bind us

The book landed on my desk with a giant thunk, the kind of thunk that nearly 700 pages of book makes. Racing Through Life, the Autobiography of Carl V. Olson.

There, grinning at me from the cover, was a young but instantly recognizable Carl Olson behind the wheel of a front-engined Top Fuel dragster, the opening invitation to read about the life and times of a guy who made a career out of drag racing, both behind the wheel and as a member of the NHRA leadership team after his time behind the wheel came to an end.

IŌĆÖve known Olson ŌĆö C.O., in shorthand to me, the same way he always addressed correspondence to me as ŌĆ£P.B.ŌĆØ ŌĆö for decades, since I came to work at NHRA in mid-1982. His driving days were behind him, but he was still heavily invested in the sport, especially on the safety and insurance front where the bulk of his work was and where his past driving experience and ŌĆ£racer mindsetŌĆØ were invaluable, and later helping forge and improve NHRAŌĆÖs international outreach. Even after his retirement, we remained email pals, and heŌĆÖs always been there to answer questions IŌĆÖve had about ŌĆ£the good olŌĆÖ days,ŌĆØ including his recent contributions to my fire burnout stories.

This isnŌĆÖt going to be a book review ŌĆö although IŌĆÖm excited to dive into it in the future, right now I donŌĆÖt have time for 660 pages about anything ŌĆö but as I began to leaf through it to look at the photos, the first thing I saw was the notation ŌĆ£for my grandchildren.ŌĆØ IŌĆÖm a sucker for anything family-related, often brought to tears reading about family ties. IŌĆÖve quizzed my mom extensively about her early years and my early years and have even committed some of it to private print, and have done my best to let my own children and grandchildren know about my youth.

I think that thereŌĆÖs a responsibility for each generation to leave behind a legacy or, at minimum, a signpost on the road for future generations to travel when their curiosity begins to pique, which might be years down the road. Honestly, until I reached my 50s, I didnŌĆÖt think an awful lot about genealogy or my roots beyond what I already knew on the surface from tales passed down. I never got to know my grandparents, and my father died when I was just 9, but what they did and how I got here greatly interests me. (That's me below in Grandpa Burgess' arms at age 1 ŌĆö my parents moved us from England to the United States not long after this, and he died a few years later ŌĆö and my dad at far right.)

While IŌĆÖm never going to pen 600 pages about my life for anyone to read, I feel like what IŌĆÖve been doing with this column over the last 16 years is my contribution to putting to print some of the many oral tales that have floated around for decades. As my drag racing heroes one by one succumb to the ails of time, those stories sometimes die with them, which is a tragedy that I have been trying to rectify and, based on the sheer number of biographical books pumped out by CarTech, thereŌĆÖs an interest for, and, in some ways, an urgent rush to commit the lives and times of these legends to print while the subjects are still able to contribute.

OlsonŌĆÖs three-year project began out of boredom during the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning with sorting through and organizing photographs, which turned into the book, which is handsomely illustrated by a ton of photos from the InsiderŌĆÖs great and generous friend, Steve Reyes.

Like me, Olson never met his grandparents and regretted not knowing about them, so he set out to make sure that his own grandkids, both still under 10, may someday be interested in knowing about GrandpaŌĆÖs life, and they wonŌĆÖt have to join 23andMe to know about him.

Before I set Olson's book into my ŌĆ£to-doŌĆØ pile, I read the foreword by our mutual great friend Greg Sharp and then C.O.ŌĆÖs introduction, which is a compelling piece of writing about what it was like to drive a front-engine Top Fueler.┬Ā

Now, you and I can watch all of the videos we want of front-engined cars of the late 1960s and very early 1970s, and I can tell you all about their history and results and other trivia, but that canŌĆÖt put you in the driverŌĆÖs seat. Olson can. With his permission, hereŌĆÖs his description of what it was really like.

I was seated behind the engine with my legs draped over the rear axle housing, with my private parts resting very near the center portion of the housing that contained the rear end ring and pinion gears. I was attired in a fire-resistant suit, gloves, boots, an open-face helmet, fire-resistant face mask with filters to minimize exhaust fumes, and a pair of war surplus aircraft goggles.

My left foot operated the cutch pedal, my right foot operated the throttle pedal, and my right hand operated the brakes with a lever. To dispatch the drag chute for primary stopping power, a parachute release ring or lever was located on the upper right-hand frame rail, and steering was accomplished by manipulating a butterfly-shaped device connected to a gearbox leading forward to a series of rods that controlled the spoked front wheels.

Because the supercharged and fuel-injected engine was located no more than a few feet directly in front of me, my field of vision was significantly obscured and limited to one side of the engine or the other. As a result, I would never have a clear, unobstructed view of what was ahead.

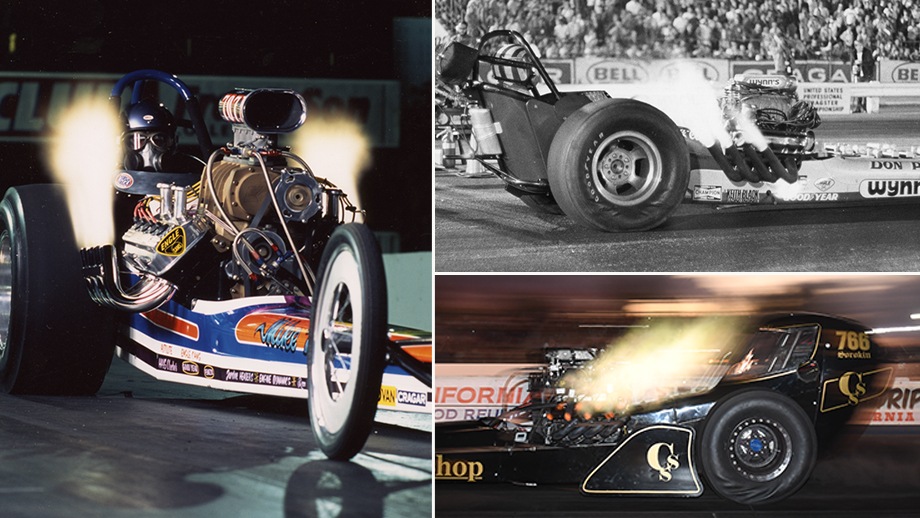

In Southern California, which was at that time the hotbed of this kind of racing, qualification runs routinely took place in the afternoon, but most eliminations took place at night under the lights. To be honest, it was the night racing that I loved most. It made all the difference in the world in how exciting it was to drive these mechanical beasts.

Because the engine involved the use of a combination of nitromethane, methanol, and, perhaps, a small dose of benzene or similar catalyst, once the sun set, the exhaust header pipes would emit flames that often grew to 2 feet tall at idle and 4 feet or more at wide-open throttle.┬Ā

When I would swap feet to launch on a run, flames would leap up at a 45-degree angle on either side of the driver's cockpit, leaving just a few degrees of vision between the rear portion of the engine and the walls of bright yellow and orange flames.

Quite often the front wheels would lift upward as the car accelerated and, on a really good run, would hover just a few inches above the track surface for the first part of the run. If too much of the vehicle weight was transferred to the rear, the result would be a giant wheelstand, and I would have to feather the throttle in an attempt to get the front wheels back to earth in order to be able to steer again. It was very rare that the car would proceed straight down the track, but under normal circumstances, steering needed to be done very gently and deliberately to prevent a loss of control.

At the time, driveline technology had moved away from lockup-style clutches that commonly involved the use of a VelveTouch-style flywheel and pressure plate and single clutch disc, which resulted in instant and continuous tire slippage and heavy tire smoke. Instead, slider clutches that involved the use of two sintered iron clutch discs, separated by a solid steel floater plate, allowed the clutch to slip, thereby preventing the tires from severely losing traction.

While the slipper clutches allowed the car to leave the starting line without the tires immediately losing traction, with the tires available at that time it was very common for them to start hazing white smoke off the tops at about a hundred feet into the run and continue doing so up to around the 1,000-foot mark. Along with my seat-of-the-pants sensations, I could quickly evaluate the density of the haze and, should it be overly excessive, backpedal the throttle to recapture optimum traction, then ease back until achieving wide-open throttle for the mad dash to the finish line.

By the time the tire haze subsided, the car would be accelerating so hard and would be going so fast that the header flames would lay back over the rear tires far enough that my field of vision would improve, and I could start to see either the guardrail, the centerline, or finish-line timing lights. It was always a relief to be able to, more or less, see where I was on the track.

Almost without exception, at about the time the tire haze would dissipate, and the car would be making its final top-end charge, oil, fuel, and water would begin to accumulate on my goggles. Sometimes it would become so intense that I would have to drive the last few hundred feet of the run essentially blind, estimate when I would be reaching the finish line at a speed in excess of 200 miles per hour and, when the time seemed right, deploy the drag chute and lift off the throttle. It was almost always necessary to pull my goggles down to safely navigate the shutoff area.

When the drag chute would blossom, the sensation would abruptly change from massive acceleration to massive deceleration and throw me forward against my lap belts and shoulder harnesses hard enough to knock the breath out of me. While it could be a bit physically uncomfortable, it was always a huge mental relief as there was a very good chance that any real danger had passed.

From time to time, the engine would experience a catastrophic failure, most likely due to one or more melted pistons or worse yet, one or more broken connecting rods. Whenever that would happen, it would be instantaneous "lights out," as I would be covered with hot oil, fuel, and other liquids. I learned very early on that under those circumstances it was advisable to wait a few seconds to remove my goggles, lest I take a full blast of hot liquids directly into my eyes.

All things considered, I firmly believe that a front-engine Top Fuel dragster was, without exception, the most evil, brutal, yet thoroughly thrilling om4 exciting motor vehicle to drive in all of motorsport, and I would not trade those days for anything.

For a guy who won a National event in a rear-engined Top Fueler and has driven as assortment of race cars (including at more than 200 mph at Bonneville), thatŌĆÖs some compelling stuff, and, as he poignantly told me, ŌĆ£Lions Dragstrip on Saturday night in a front-motor Top Fuel car was absolute nirvana for me.ŌĆØ You can find Olson's book on or in the Kindle bookstore.

ItŌĆÖs certainly not the first time IŌĆÖve heard this front-engine love story. A few years ago, Don Prudhomme told me, ŌĆ£The front-engined dragster, without a doubt, was the most thrilling, most fun thing you could ever possibly drive. The engine was right in front of you; you could see everything ŌĆö the exhaust pipes, the blower. There were no starter motors or any of that jazz. The way you started them was push-starting. A car or truck would be behind you, youŌĆÖd get going, let the clutch out, feed a little fuel, shut it off, and hit the starter switch, and it would go bahhhh-bup-bup-bup and pull away and then start idling. It was a real turn-me-on-er. The girls fell out of the stands. It was pretty cool, I gotta tell you.ŌĆØ

And while none of us who havenŌĆÖt done it will ever really know what it was like to drive a vintage front-engine Top Fueler, newer generations have the chance of a similar experience in the NHRA Hot Rod Heritage Racing Series, including guys like Adam Sorokin, who followed in the footsteps of his famous father, Mike, by slipping into the cockpit behind a nitro-burning monster.

Sorokin was just 1 when his father was killed in a racing accident in 1967, sadly one of many who lost their lives in those temperamental machines at a time when safety wasnŌĆÖt what it is today. So, in this homage to the front-engined Top Fueler, I was interested in what itŌĆÖs been like for him to saddle up in his fatherŌĆÖs fireboots and experience the thrills and sensations that his dad did.

"My mom made sure that I went to the drag races to show me what he did," he said. "It was really important to her that I knew who my dad was, what he did, and what he was good at. I was only 1 year old when he died, so I don't have very many memories of him, so she would talk to me a lot about my dad, and how good of a driver he was, and just what kind of person he was.┬Ā

"She would take me to Orange County [International Raceway], which is where he was killed, and at the time, the Mike Sorokin Memorial Award was going. She presented it for the first few years, and then when I got old enough, I started giving it out. I think the first time I gave it out was 1973 to Tom McEwen [pictured below]. I was always fascinated with who my dad was because my mom had given me all these magazines and 8x10 pictures of him racing, so I was always kind of turned on by that and always wanted to race."

Although Adam's initial forays into racing came in go-karts and other corner-turning endeavors, he ended up in drag racing, where he belongs, first in a Super Comp car at the Frank Hawley Drag Racing School and then in Alcohol Funny Car before Top Fuel.

"As I was getting older, my mom was not really hot on me racing, because she had lost her husband," he remembered. "Fast forward to1985 and she's dying of stomach cancer at 37, and about a week or two before she dies, we have a talk. And she's like, 'Listen, I know you've always wanted to race. I'm not going to be around to worry about you much longer. Please follow your dreams and just be careful.' And, that was very important to me.

"I basically went into drag racing to understand my dad. You know, it's like, this is what he did. I didn't know much about him, and this was an avenue that I could take to understand him more, and understand why he loved it, and all those kinds of things. When I finally got to the Frank Hawley school, I was really turned on by the whole thing, the sensory experience of drag racing.ŌĆØ

After a few years in an Alcohol Funny Car, he got his first nitro ride in John BlanchardŌĆÖs front-engined Top Fueler.

He remembers it vividly: ŌĆ£My last licensing run in front-engine Top Fuel car was at nine o'clock at night at Sacramento, and it was hard to see, but I get in that car, I swapped feet, I get going down the track and there's 6- or 7-foot flames, but they feel like they're 14-20 feet. I'm going down the track and the flames are up, and I'm driving the car, and I find myself looking at the flames, and I was, like, all of a sudden I had to kind of mentally slap myself in the face and go, 'Hey, you have to drive this car down the track,ŌĆÖ and so, I get back on the wheel and I'm driving the car, and I make the run. And I was sold.

"The modern front-engine Top Fuel car makes maybe 3,500 horsepower, roughly double what they made back in the ŌĆś60s, but they still have the same size tire on it and the driverŌĆÖs still in the same location. You just have some better engine parts and better chassis parts and stuff like that, and you're not smoking the tires anymore, but there just isn't anything better in my opinion.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve driven Funny Cars, and I like the body going on top of me and all that, and itŌĆÖs all kind of cool, but the dragster itself is so pure in the form of a quarter-mile race car in the way itŌĆÖs designed. It's long because of the weight transfer and doesn't have anything on it that it shouldn't have and then you hit the throttle and the rpm comes up, and then the clutch engages and you feel the traction as it's going down.

ŌĆ£The cool thing about the nostalgia dragsters is that they really don't get pushed into the ground much at all; we don't have the wing of a modern Top Fuel car or the body on a Funny Car. You have these little canard wings that maybe make 500 or so pounds of downforce, so you're driving on top of the track, rather than being pushed into it. And when you're on top of the track, that car wants to move around, and it wants to do things that you have to listen to and drive so much more with your ass than you ever do with your head. When the car is shaking, you're the closest conduit to it, or when it spins, you feel it, and it's the finesse of getting one of those cars down the track [that] is still pretty important.

ŌĆ£But, man, the way it hits. the way it sounds, the flames out the pipes. Once I started driving a front-engine Top Fuel car, I was like, ŌĆśOh, this is why my dad did this. Absolutely. This is why he loved it. This is why I love it.ŌĆÖ His love turned into my own love, and then I continued to do it because I just wanted to be good at it. I think the thing between fathers and sons is sons always look up to their fathers and want to follow in their footsteps, but at some point, I think sons want to compete with their fathers. Even though I couldn't do that, you want to get good enough ŌĆö and I don't think anybody was better than Mike Sorokin at leaving and driving; to me, he's the best, right? ŌĆö and then, as a son, you want to get to that point where you go, ŌĆśDamn, I'd like to line up against him.ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ

Adam will never get the chance to race his dad, but with a 23-year-old son, Mike ŌĆō named after his own dad ŌĆō showing an interest in the sport, maybe it could happen for him. Although Adam never got the benefit of hearing from his dad firsthand how to drive a front-engined car, he had plenty of mentors in people like Pat Foster, Bill Alexander, and Bob Muravez to help him learn the ropes.

ŌĆ£My son and I have had those talks," said Adam, "and I told him, ŌĆśYou don't have to do it because of what your last name is or because of me or because of your grandfather. You need to follow your own rainbow. I always wanted to do this. If you don't, I will think of you just as much, if not more, as a man. If you follow it, you have to have your own passion for it, but it takes a lot of work to get here. Nobody's gonna give you a ride just because your name is Mike Sorokin. You just have to do the work.'

ŌĆ£But yeah, he went to Frank HawleyŌĆÖs school and just killed it. ItŌĆÖs interesting to see somebody that's never been in that kind of a car just do it and do it really well. I think we all want our dads to be proud of us and, for me, having a father who was so successful, your first thought is ŌĆśDonŌĆÖt suck,ŌĆÖ because weŌĆÖve all seen that, but even following in his footsteps for my own reason, I always hoped he was looking down and smiling.

ŌĆ£I had that feeling in the final round at the March Meet in 2010. It was cloudy all weekend, and we didn't finish the race until Monday. I was strapped in the car, and we were getting ready to fire, and I remember thinking about it, because he had won that race, and right before we fired the engines, the clouds broke and the sun hit the track. And I think that's probably the time where I've never felt my dad's presence more. I definitely felt him there. I wanted to feel him there and for him to be proud of all IŌĆÖve accomplished.ŌĆØ

Bob Skinner, Tom Jobe, and Mike Sorokin ŌĆö the Surfers ŌĆö celebrate their March Meet win in 1966.

For all of us dads and sons, itŌĆÖs all part of the legacy that we pass on, along with the last name that we hope will keep adding branches to the family tree. As some of you know, my son followed me into playing hockey, and I had the ultimate thrill of playing on the same team and sharing championships with him, and I was never more choked up than when he showed me a large tattoo heŌĆÖd gotten on his bicep with our last name. It was very touching that he was proud of the last name and of the family from which he came.

IŌĆÖm glad that front-engined nitro dragsters are still part of the NHRA scene that we can all revisit at the Heritage events and that there are people like Olson and Prudhomme reminding us of how cool they were and younger guns like Sorokin continuing to add to the legacy of one of the most iconic vehicles in our sportŌĆÖs history.

Phil Burgess can be reached at┬Āpburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the┬ĀDRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the┬ĀRandom Dragster Insider story generator