The first 300

|

Two weeks from today will mark the 20th anniversary of the breaking of one of drag racingŌĆÖs great barriers, Kenny BernsteinŌĆÖs shattering of the 300-mph plateau at the 1992 Gatornationals. While it took 15 years ŌĆō 1960 to 1975 -- to go from 200 to 250, it took just 17 to go the next 50 to 300, a pretty amazing feat given that itŌĆÖs accepted that it becomes exponentially more difficult to overcome the forces of nature ŌĆō most acutely, aerodynamic drag -- the faster you go.

I remember that although it was a much-anticipated barrier breaking, it wasnŌĆÖt expected, at least not that early in the decade. The handwriting was surely on the wall but had only been penciled in by hopefuls like me. And with good reason.

After Don Garlits recorded the first 250-mph pass at the 1975 season finale in Ontario, Calif., there was a period of speed stagnation in Top Fuel. No one ŌĆō not even ŌĆ£Big DaddyŌĆØ ŌĆō topped 250 mph in 1976 (Shirley MuldowneyŌĆÖs 249.30 was the yearŌĆÖs fastest speed), and there were fewer than a dozen 250-mph passes through the end of the decade. In fact, it took a whopping seven years for all 16 places in NHRAŌĆÖs 250-mph club to be filled. By the end of the next year, 1983, the best speed was just 257.87 mph (run by both Muldowney, in Gainesville, and Jody Smart, at the IHRA event in Bristol).

|  |

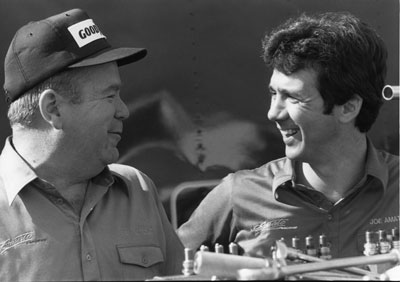

| Using a design suggested by IndyCar engineer Eldon Rasmussen, Joe Amato crew chief Tim Richards (above left) mounted a wing higher than and further behind the rear wheels than ever seen, taking advantage of the simple principle of leverage to get downforce without drag. (Below)╠²Amato and Richards made history as the first to exceed 260 and, later, the first over 280 mph. | |

╠² | |

Then came 1984 and the introduction by Joe Amato and crew chief Tim Richards of the now-mandatory laid-back tall rear wing that took advantage of leverage to provide ample downforce with less drag and quickly pushed Amato past the 260-mph mark at that yearŌĆÖs Gatornationals (are you sensing a trend here surrounding Gainesville?).

As Top Fuel racers experimented with small front tires, bigger rear wings, cockpit canopies, ground effects, and full and partial streamliner bodies, the speed record shot up. Garlits broke the 270-mph mark just two years later -- again in Gainesville ŌĆō with his spoon-nosed, enclosed-cockpit Swamp Rat XXX, and just a year and a half later, Amato became the first to exceed 280 during qualifying at the 1987 U.S. Nationals. A year and a half after that, at the 1989 Winternationals, Connie Kalitta became the first to crack 290 mph. By yearŌĆÖs end, the╠²late Gary Ormsby had pushed his Lee Beard-tuned Castrol GTX dragster to 294.88 mph in Dallas. By the end of 1990, Ormsby had run 296.05 mph, in Topeka that September.

Although the numbers continued to creep upward, the pace slowed. Logic almost demanded it. What people forget is that with OrmsbyŌĆÖs passing the next year, so seemed to die the hopes for a swift overtaking of the 300-mph mark. The best run of 1991 was just 293.15 by Don Prudhomme; ŌĆ£the SnakeŌĆØ also had the next two best runs, 292.11 and 291.45.

At the end of 1991, Bernstein and crew chief Dale Armstrong made a canny move, hiring Wes Cerny, who had tuned Roland LeongŌĆÖs Jim White-driven Hawaiian Punch Funny Car to that classŌĆÖ first 290-mph run earlier that season. CernyŌĆÖs cylinder-head knowledge and extensive work in the magneto department immediately paid dividends.

In Houston, at╠²the event just prior to the Gatornationals, Bernstein ran 296.93 mph despite dropping a couple of cylinders. At the same event, Mike Dunn ran 297.12, the fastest pass in drag racing history, and Pat Austin reset the national record to 295.27. Suddenly it was game on for Target: 300 as NHRAŌĆÖs media blitz went into overdrive.

At first, all was relatively quiet in Gainesville. Austin reset the track record to 292.39 during Thursday's qualifying, breaking BernsteinŌĆÖs 289.57 from 1991. Bernstein's best pass was just 291.26. Not much happened in FridayŌĆÖs first qualifying session, either, but Bernstein was in the first pair of cars down the racetrack in the second of two qualifying sessions that day.

As Wes Cerny, left, and Dale Armstrong looked on, Kenny Bernstein made drag racig history March 20, 1992, with the first 300-mph pass. |

|

Bernstein and crew accepted a $50,000 award for the╠²feat. |

At 4:44 p.m. March 20, Bernstein and qualifying mate Al Segrini left the line together. SegriniŌĆÖs mount was quickly up in smoke, giving Bernstein the stage all to himself. Just 4.823 seconds after leaving the╠²starting line, he not only had recorded the quickest e.t. in class history, but also its first 300-mph pass.

"The car left good and was running hard in the middle of the track, but the engine got a little sour right in the lights," said Bernstein. "Normally, I would have lifted, but I told myself to drive it all the way out the back door because it might be the run. I didn't care if it dropped cylinders or not. I knew I was going pretty fast because I had to drive farther than I normally do to make the turnoff."

(Bernstein was dead-on --╠²a cylinder stopped firing four-tenths of a second, or about 200 feet, before the finish line.

"I didn't really want to tell anyone that it had dropped a cylinder and still ran 300 because everyone will say, 'Yeah, right,' but it did," Armstrong confided.)

Bernstein (as you will read later) initially didnŌĆÖt know he had made history but made it official when he backed up the 301.70 for the national record with a 299.30-mph blast in the quarterfinals of Sunday's eliminations after running 298.30 in the first round. Bernstein ran 300 mph twice more that season, in Englishtown (300.40) and Indy (301.20), and it was almost 11 months later, in February 1993, before someone else ŌĆō Doug Herbert at the Winternationals ŌĆō also recorded a 300-mph pass.

Since then, 300 has become a common occurrence in both nitro classes ŌĆō the first 300-mph Funny Car pass was at the end of 1993, in Topeka ŌĆō but the first one is the one that people will always remember.

"Being the crew chief on the first car to run 300 means more to me than any national event win or any Winston championship," Armstrong said at the time. "There isn't any question at all. People will forget what years we won the Winston championship, but they'll never forget when 300 was run and who did it."

HeŌĆÖs right.

|

All these years and championships later, Bernstein still hangs his hat on the pass as the highlight of a highlight-filled career. He took part last week in a national NHRA teleconference and talked at length about the accomplishment and where it rates in his career.

ŌĆ£I think it would be at the top. It is certainly the top of the pole. Fortunately for us, we got to accomplish a whole lot with great crew chiefs and teammates through the years. That's the one thing that everyone seems to remember across the board, whether it be drag racers or just the normal person that follows the sport in general that knows a little bit about racing. It was a great accomplishment on the day, came totally unexpected, which was better, because it caught everybody, including ourselves, off guard.

ŌĆ£It was a beautiful day, No. 1. It was pretty much ideal conditions. In Gainesville, we get the luxury when the conditions are good there, a lot of trees, oxygen. Oxygen makes power in these cars. The coolness of the day was good. We had not even talked about this being a 300-mph run. We hadn't talked about getting to 300 other than we wanted to. It wasn't like it was preplanned that this run was going to be the one. The car left the starting line, ran really good, got to the finish line. I coasted to the turnoff area.

"I've told this story many times, but it's true. When I turned on the turnoff, the guy that helps you, one of them was holding up three fingers. The first thing I thought was that he meant we qualified No. 3. I was pretty disappointed because I thought it was a No. 1 qualifying run because it ran pretty well. He held up those three fingers. Like I said, I was a little disappointed. He reached in and pounded me on the chest and said, ŌĆśYou just ran 300.ŌĆÖ It didn't dawn on me at first. I said, ŌĆśDo what?ŌĆÖ That's what the three fingers were. From that point on, it was just ecstatic, as you can imagine, it was craziness. Again, it was so unexpected that we were going to do it, anybody was going to do it, that day. We had all been running 296, 297, but to jump to 301, that's a big step to make that jump; it's really hard. Dale Armstrong, my crew chief, he tells the story, he looked up and saw the lights, saw the 4.82 seconds. Turned around and started walking to the pits. The team members had to grab him and tell him it ran 301 mph. That's what I mean by it being unexpected."

Unexpected, but well-remembered.

Thanks for reliving that great moment with me. I'm hoping that in just a few days we might see more history in Gainesville, perhaps the sport's first 200-mph Pro Stock Motorcycle╠²pass. I'll be heading╠²to G-town Thursday and╠²be╠²there all weekend, so there won't be a column Friday. Travel to╠²and from the East Coast is always a day-killer, so I'm not yet╠²even going to promise a column for next Tuesday, either. We'll see how it goes. Thanks again for reading.

╠²