Pedal power: Mike Dunn's first drag race

|

Like a lot of you, my first introduction to Mike Dunn came in the movie theater, where the future 22-time national event winner was racing his Schwinn Sting-RayÌýin bicycle drags, complete with a blossoming chute, in the drag-cult hit Funny Car Summer.

I've seen the footage numerous times but never had a chance to ask Mike about it until last week, when he was sharing with me his thoughts for his Final Take column in National DRAGSTER about how the reaction time in 91°µÍø Pro drag racing is so misleading based on how the car's fuel and clutch systems react, how quickly the driver leaves, and especially how deeply the driver is staged, skills Dunn first mastered on two wheels.

Dunn was 14 when the bike-drags craze hit Southern California in 1971, and tournaments that drew hundreds of competitors were set up in the parking lots of local malls. The kids were separated by age groups (5-7, 8-10, 11-13, 14-16, and 17 and up, plus two classes for girls) and raced over a 50-yard course.

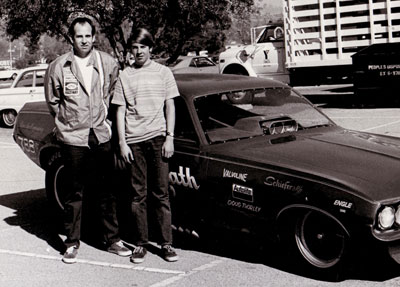

Young Mike Dunn had a bit of an ace up his sleeve in tech advice from his Funny Car racing father Jim, who displayed his Dunn &ÌýReath Barracuda at one of the bike-drags events, much to the envy of young Dunn's peers. |

Ìý Kids of all ages with all types of bikes could take part in the races, which often were decided by razor-thin margins. |

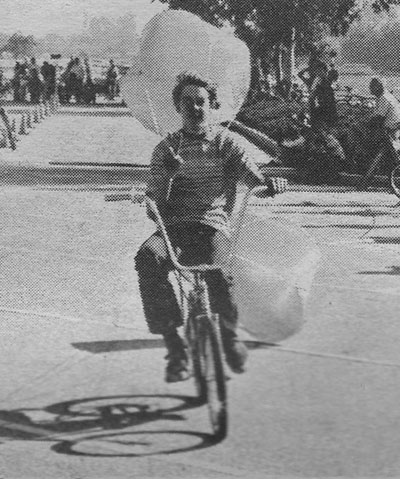

Ìý Dunn went almost undefeated in 1971, losing at just two of 30 events. Ever the drag racing-influenced showman, Dunn deployed a pair of braking chutes and flashed the V-for-victory sign at the end of this winning run. |

The starting system was simple and would only tell the starter whether a rider red-lighted. Made up of a pair of 10-inch-wide copper plates that were in contact when a rider was staged and broken when the rider left, it didn't take drag-savvy young Dunn long to realize how to take advantage of the system by shallow staging for a running start (unlike today's NHRA systems, the bike-drags e.t. clock started when the Tree turned green, so a good reaction time was paramount to having a good elapsed time) or how to "tune" his bike for maximum performance.

"My dad hardly ever went to the races with me, but he did tell me to experiment with gears," said Dunn. "The races were run in shopping centers, and sometimes it was an uphill track for safety. If it was an uphill track, I'd change my sprockets to put a lower gear in; none of the other kids knew that or understood that."

Dunn was runner-up at the first event he attended, then went unbeaten for nearly 30 races before being surprised by a competitor almost as wily as he.

"This guy came out with a 10-speed bike that he's turned into a two-speed using an adjustment screw on the derailleur so that he only had 1st and 2nd gear," recalled Dunn. "He'd moved the shifter lever right up to the right brake handle, and this guy flew. Up until he showed up, I was just going through the motions because I was winning everything.

"I had beaten this guy the week before, and he went home and did his homework and came up with this two-speed deal and ran 5.90 and broke my back in the semifinals. At the next race, he had it even more figured out and went like 5.50 in qualifying, but he didn't understand how the starting system worked.

"This was the race they filmed for Funny Car Summer, and I had canard wings on my bike and a big ol' banana seat for the parachutes.

"The first round, I ran like a 6.15 and then a 6.08 and just barely got by the round. In the semi's, I had to race this guy's buddy, who had run like a 5.80-something, so I got back to the pits and started pulling all that crap off my bike to lighten it. The producer came by and was not happy, but I told him he could forget about the movie -- I wanted to win the race -- which is why in the movie they ended up showing the second round as the final. After stripping all that stuff off, I went 5.82 and beat that guy."

Knowing he was in a performance hole for the final, Dunn employed a little gamesmanship to level the playing field.

"For the final, I staged at the back of the plate and did my usual deal of leaving before him, but he kept red-lighting – they'd give you two free red-lights and disqualify you on the third -- and he couldn’t figure it out. He got two red-lights and I didn't have any, so I knew I had nothing to lose by going for it, and I must have hit it just perfect.

"I had my bike geared really low so it was real fast off the line, but by three-quarter-track, I was running out of gas, and here he comes. I beat him by inches, 5.78 to 5.79. I weighed all the parts later on an old fishing scale my dad had in the garage, and I think it weighed about seven or eight pounds, which is a lot for a bike."

Like any drag racer, Dunn could see the handwriting on the wall and knew that he had to step up his technology for the next season and built his own "2-speed 10-speed" but was sidelined by injury before he could ever race it, which just may have set in motion his drag racing career.

"I was practicing in front of the house one night, and I had my head down when I shifted and ran right into a curb and landed on a fire hydrant and broke my collarbone. The bike-drags thing was kind of dying because BMX had just started. I had asthma and was a good sprinter but didn't think I could do the BMX deal. I was getting ready to quit bikes anyway because I was almost 16 and ready to start racing go-karts because my dad told me if I raced a go-kart for a couple of years, he'd put me in his car.

"Still, I had a lot of fun with the bike drags," he reflected. "I thought it was kind of cool; it was some of the most fun I've ever had."

|

The drag racing media bunch is a pretty tight family, and it's been a rough few months for us since December when we lost our court jester, Bill Crites. This morning comes news that Bob Hesser, our Division 3 photographer and genuinely one of the nicest and most humble guys you'd ever meet, passed away after being taken ill this weekend.

Jacklyn Gebhardt-Still, Comp winner in Houston and owner of Midstate Dragway in Bob's home division, perhaps said it best when she told me this morning, "He would make my local racers feel like they were racing at a national event. It's a terrible loss."

Bob, who contributed photos to National DRAGSTER and, through his employment with Auto Imagery, to NHRA.com, was just 46. His passing leaves a huge void for all of us who knew him, and his passing, along with the loss of former Safety Safari and Hot Rod magazine lensman Eric Rickman (Jan. 24) and giant health scares for veteran photographers Tom Schiltz, Auto Imagery's Dave Kommel, and Steve Reyes, reminds us how fragile life can be sometimes.

Godspeed, Bob.