History lesson in a book

|

Our dear ol' pal Richard Brady, a longtime Division 3 photographer and a steady source of dependable and indispensable help to the National DRAGSTER staff at more than a dozen Full Throttle Drag Racing Series national events this season, has been combing through his photo files and posting great old pics on his Facebook page, and his treasure hunt also turned up a gem that caught my eye: a 1972 NHRA media guide. He shared it with me at the Summit Racing Equipment NHRA Nationals in Norwalk.

I have a nice collection of media guides from the early 1990s, and they surely have changed throughout the years. For those not familiar with this type of publication, it's a compilation of facts and information that helps members of the media do their job. Today's NHRA media guides have hundreds of pages with extensive driver bios and career records, historic points listings, a recap of the previous season, and information about NHRA, its series, the cars, and much more. They're an invaluable tool even for us supposed know-it-alls.

I wasn't aware that NHRA had a media yearbook, as this one was called, way back then. In fact, just last year, Director of Media Relations Anthony Vestal and I were trying to figure out what might have been the first year of the media guide, and I'm sure we didn't arrive at the early 1970s.

Brady actually had a 1971 media yearbook on him, but the 1972 book seemed more well-prepared, so I eagerly dove in, and even a jaded history nut like me was thrilled at the time-capsule contents.

The first thing that caught my eyes was a staple of every media guide, a list of the sport's winningest drivers. Here wasÌýthe score heading into 1972:

Ronnie Sox:Ìý15

Don Garlits:Ìý7

Gordon CollettÌý: 7

Dave Boertman:Ìý6

Gene Snow:Ìý6

Don Prudhomme:Ìý5

George Montgomery:Ìý5

Ray Motes:Ìý4

Don Nicholson:Ìý4

Bill Jenkins:Ìý4

At first brush, my thought was, "The all-time winningest driver has only 15 wins?" John Force, of course, is the all-time leader now with 126, and 15 doesn't even get you in the top 25 anymore; you have to haveÌý36 Wallys on the shelf to make the top 25 these days. How far we've come in 37 years. (Fifteen wins would, however, still get you an 11th-place tie with Al Hofmann among Funny Car drivers, rank you 13th in Pro Stock, and tie you with Dick LaHaie for 14th in Top Fuel. ... 77th overall still.)

|

Of course, once I got my head out of … well, you know … I realized just what an amazing number Sox's 15 wins were. To that point, there had only been 49 national events, and Sox had won 15 of them, or nearly a third. And, truth be told, he had won 15 of them in 37 races, beginning with his first, in Factory Stock at the 1964 Winternationals. And he had twice as many wins as the next driver!

By my count, the Norwalk event was the 680th national event in NHRA history, so -- apples to oranges -- that would be like Force having more than 200 wins. Of course, Force didn't get his first win until race No. 220 in NHRA history, so he's won 126 in 460 races, which ain't shabby either.

As I continued to read through the guide, there was a whole section on new rules for that season, and a lot of it had Mr. Sox's signature all over it. Although Sox had added five Super Stock wins, he won nine times in the newly created Pro Stock class in 1970 and 1971, including six of eight in 1971. Mopar had grabbed a seventh win with Mike Fons' Challenger; Nicholson's Maverick had the only non-Mopar win.

To combat the dominance of Sox's Hemi, three weight breaks were added to Pro Stock in 1972 "with an eye for increasing popularity and competition."

Through the class' first two seasons, all cars ran on a 7-pounds-per-cubic-inch weight break regardless of engine type or design. Beginning in 1972 and lasting until 1981, NHRA controlled runaway situations with the weight breaks, which became a huge source of controversy (as they can be today in Pro Stock Motorcycle) and a real pain for the NHRA Tech Department.

NHRA kept the existing 7-pound break for cars with staggered-valve wedge engines like the 396 Chevy and 427, 454, and 351 Cleveland Fords but socked it to the Hemis (and the SOHC and 429 Boss Ford engines) with a 7.25 break. At 426 cubes, that amounted to a 106-pound weight increase. And it showed. Only Don Carlton was able to score for Mopar in 1972 while Bill Jenkins won six times for Chevy thanks to the addition of the third break and some innovation by NHRA.

Automakers had just begun to focus on smaller compact models, and NHRA wanted them to have a place in the innovative class. In addition to adding a 6.75-pound break for smaller wedge engines such as the 302, 327, and 350 Chevys, 340 Chrysler, 427 and 352 Fords, and 360 and 390 AMCs, cars with a wheelbase of less than 100 inches – such as the Pintos, Vegas, Colts, Crickets, and Gremlins -- were allowed a minimum weight of 2,000 pounds as long as they used 366-cid or smaller engines; cars with a wheelbase of more than 100 inches had a 2,400-pound minimum weight with no ceiling on cubic inches. (Of course, no one would build a 500-cid engine like we have today and carry a 3,500 weight.)

The weight breaks were finally abandoned in 1982 when NHRA switched to a mandatory 500-cid powerplant.

Another interesting change in 1972 was the absorption of all 1971 Stock classes into Super Stock to create a "strictly stock" class below it. Today's Stock cars are allowed many go-fast modifications and engine tweaks, but if you ran a Stocker in 1972, not only weren't you allowed such basic amenities as headers, slicks, racing cams, and manifolds, but you also had to drive the carÌýto the track instead of trailering it. Wow.

|

The guide also includes a timeline of great accomplishments not necessarily listed in the current version, which tends to present a bigger-picture/top-story kind of timeline. The 1972 guide includes these milestones; some of the first may be disputed in other circles but nonetheless make for a handy reference guide for your future bench racing sessions (items in quote marks are reprinted as they appeared):

1953: First 140-mph speeds recorded

1954: 166 events sanctioned; introduction of first comprehensive insurance program

1955: Flywheel shields (scattershields) made mandatory

1956: First rulebook published

1957: First eight-second elapsed times

1958: Don Garlits records first unofficial 180-mph clocking

1959: "Parachute braking device introduced, soon made mandatory for all cars running in excess of 150 mph"

1960: National record program established; spectator count exceeds 1 million

1961: Nationals moves to Indy

1962: Tommy Ivo runs first seven-second pass, a 7.99 at San Gabriel; Tommy Grove makes first 11-second clocking with a stock car, 11.93 at Fremont; first "traction mix" compound for dragstrip asphalt announced by NHRA and Shell Oil

|

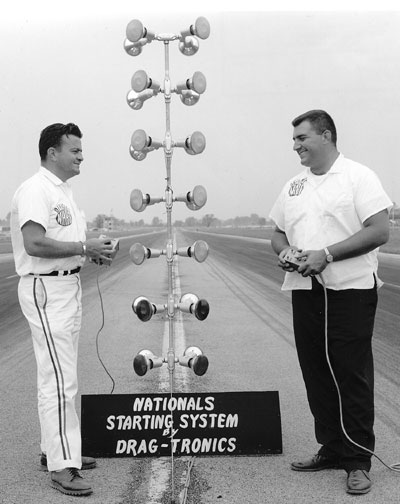

1963: "NHRA lifts ban on special fuels and re-creates fuel dragster class"; first live televising of a major drag race as the Nationals is televised on Wide World of Sports; true handicap starts introduced with Christmas Tree

1964: Driver-licensing program established with testing procedure required for dragster drivers; Manufacturers Cup program established

1965: "Forerunners of today's Funny Cars make their appearance in the form of FX class machines designated by NHRA"

1966: First seven-second run on gas as John Peters' Freight Train runs 7.99; Shirley Shahan becomes first female national event winner at Winternationals; Connie Kalitta runs "first accredited 220-mph pass" at 221.12 in Ford-powered dragster

1967: 1,315 carsÌýset entry record at Nationals; Ed Miller scores richest purse ever by a driver for winning Stock world championship, $10,000, which includes bonus posted by Hurst; first official six-second pass, by Don Prudhomme in winning Springnationals; SEMA-approved chassis required in Top Fuel; contingency program unveiled; first $100,000 cash purse at Nationals

1968: More than 2,500 NHRA-sanctioned events are completed; World Finals shown live around the country on closed-circuit TV; $150,000 purse at Nationals

1969: First all six-second 32-car Top Fuel qualified field at Springnationals in Dallas

|

1970: First $300,000 purse, at Springnationals; Leroy Goldstein makes first six-second Funny Car run, a 6.92 in Indy

1971: "Advent of rear or mid-engine dragster offers first major concept and design change since debut of slingshot dragster"; onboard fire extinguishers made mandatory in Funny Car; Jerry Ruth makes history as the first driver to win in two classes at same race, scoring in Top Fuel and Funny Car at a Division 6 event; Wally Parks, Don Garlits, and Ronnie Sox visit the White House during a special presidential reception for auto racing; Pro Start Tree introduced (one amber instead of a countdown of five ambers); fire burnouts banned

Today's media guides also include a glossary to help neophytes decrypt the sometimes arcane vernacular of drag speak, but I got a real charge out of some of the glossary entries from the 1972 edition, which broached over into pop culture. These are the exact definitions provided; I couldn't make this stuff up.

Anchors: brakes

Bad scene: unpleasant situation

Bash: a racing event

Boss: great, outstanding!

Eyeball: inspect or examine something

Fuzz: police

Handler: driver

Honk: run fast

Joe Lug Bolt: competitor who runs only on weekends, periodically

Juice: special exotic fuel

Lunch: damage engine or other parts severely

Nerd: not hep

Out to lunch: not with it

Ratchet jaw: person who talks too much

Ìý

That was boss! What a great find. Thanks to R.B. for showing me the guide and allowing me to spend a few days with it. Okay, ol' ratchet fingers here has to honk it on outta here to finish his National DRAGSTER work from the Norwalk event or the copy editors will think I'm a nerd. That would be a bad scene. I'll be back later this week with a new column, which tentatively is planned as the next installment of the Misc. Files, the letter H. You can eyeball it here Friday!

Ìý