If the Shoe fits ...

|

Even as our Favorite Race Car Ever poll heads toward the final rounds, IŌĆÖm still getting e-mails asking how I could possibly have forgotten to include this particular car or that car in the polls. The perceived slights run the gamut from obscure cars that even I havenŌĆÖt heard of to some more famous cars that actually impacted the sport in different ways, and my answer is always the same: ItŌĆÖs not a best-ever poll or even most-important poll; itŌĆÖs a poll of favorites submitted by the readers of this column.╠²This was never intended to be a poll proclaiming the best anything, except maybe best-liked or best-remembered.

IŌĆÖm brought to this point not by the derision of a few ŌĆō I rather enjoy the exchange of opinions ŌĆō but simply by the contemplation of what intangible makes up a favorite car in the minds of many. For many, itŌĆÖs youthful memories, paint schemes, and body design, and, although a carŌĆÖs ŌĆ£kickassednessŌĆØ also is a factor (i.e., Don PrudhommeŌĆÖs Army Monza), itŌĆÖs not the overwhelming factor. How else do you explain ŌĆ£Jungle JimŌĆØ LibermanŌĆÖs Vega ŌĆō which won just one national event and never was a championship contender ŌĆō whipping Raymond BeadleŌĆÖs Blue Max and ŌĆ£SnakeŌĆÖsŌĆØ Monza, both of which won multiple world titles and handfuls of events?

YouŌĆÖll notice, too, that in the 1980s and beyond poll above, there isnŌĆÖt a single car from the current decade, a nod in part, no doubt, to the sameness of the cars and their being limited largely to national event competition, but I wonder how this same poll would change if it were held 10 or 20 years from now. Specifically, how will Tony SchumacherŌĆÖs U.S. Army dragster be remembered?

ItŌĆÖs undoubtedly the killer car of this year and arguably of this decade, at least from mid-2003 on. In case you missed it, Schumacher won his 50th Top Fuel title last weekend in Brainerd, bringing him to within two victories of tying Joe Amato as the sportŌĆÖs winningest nitro-rail driver, a prestigious mantle that Amato has held for nearly 12 years since passing Don GarlitsŌĆÖ 35-win total at the 1996 Finals.

IŌĆÖve asked this question a lot, of racers and fans alike, and always received the same answer, and it seems to be indisputable that no matter the number of wins, no driver but Garlits will ever be declared as the sportŌĆÖs all-time greatest Top Fuel racer. ThatŌĆÖs certainly no knock on ŌĆ£JoltinŌĆÖ JoeŌĆØ or ŌĆ£the MachineŌĆØ but rather a bow to GarlitsŌĆÖ did-it-all-myself method of racing. He built the cars, he wrenched on them, he tuned them, and he drove them. It's doubtful that Amato or Schumacher ever even briefly did more than two of those, but donŌĆÖt blame them. Garlits did it in a different era; back then, that was the way you raced.

Amato didnŌĆÖt have to get his hands dirty, nor did he try to be Mr. Everything; he was a millionaire businessman racer╠²smart enough to hire very talented people like Al Swindahl and Tim Richards to do those things for him while he sought sponsors and drove a race car about as well as one could drive it.╠²With the responsibilities that befall a guy with a huge and visible sponsor like the U.S. Army, not to mention public-relations duties for them and NHRA, Schumacher also is best left doing what he does: Driving and saluting our troops. It would be silly to see him bust a knuckle between rounds.

Still, IŌĆÖm going to agree with the popular thought these days that while Schumacher may never be proclaimed the best Top Fuel racer or even driver (there is a difference), his team may certainly be the best Top Fuel team ever assembled. Sure, Garlits had Herb Parks and T.C. Lemmons and Amato had ŌĆ£the General,ŌĆØ Jeff Rodgers, and the Walsh brothers, but from stem to stern, the Army team seems flawless. The sponsor and operation are top notch, the crewmembers put the engine back together flawlessly, crew chief Alan Johnson seldom misses a tuning call, and Schumacher is one of the steadiest drivers out there.

╠² | ╠² |

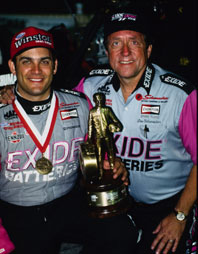

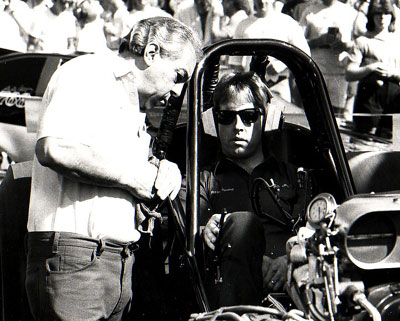

Okay, Schumacher fans, time to haul out those old pre-crew-cut photos of "the Sarge" -- (left) as a fresh-faced Top Alcohol Funny Car rookie in 1995 and (right) enjoying his first Top Fuel win in Dallas in 1999 with father Don. | |

In retrospect, itŌĆÖs pretty surprising that Schumacher is the guy weŌĆÖre talking about to be crowned╠²the new king of Top Fuel wins. People forget that Schumacher suffered an almost John Force-like victory drought to begin his career, finishing as runner-up in his first eight finals before finally reaching the winnerŌĆÖs circle at the 1999 Dallas event, where he defeated Scott Kalitta to win his first title. Interestingly, Schumacher spotted Amato exactly 50 victories before he won his first and, truthfully, has done the majority of his winning in the last five years, since hiring Johnson in mid-2003, when he has amassed 43 of his 50 wins. With seasons like his 10-win campaign of 2004 and nine victories in 2005, itŌĆÖs no surprise that Schumacher collected 50 wins in 37 fewer races than it took Amato (260 to 297).

Oddly, Schumacher has won 47 of his 50 Wallys after Amato unexpectedly retired at the end of the 2000 season, one year short of his planned retirement, due to problems with his eyes, much in the same way that Amato scored the lionŌĆÖs share of his Top Fuel wins ŌĆō 45 out of 52 ŌĆō in a Garlits-free environment after Garlits retired (again) in mid-1987 after backflipping Swamp Rat XXXI in the lights in Spokane, Wash., his second such blowover in less than a year, and just a few months after ŌĆ£Big DaddyŌĆØ racked up his 35th and final win at that yearŌĆÖs Winternationals, defeating ŌĆō who else? ŌĆō Amato in the final round. What's the old axiom about nature abhoring a vacuum?

With wins in five of the last six events and nine overall this season, Schumacher is on course to have perhaps the greatest Top Fuel season on record and looks sure to break his 2004 record of 10 event wins and Kenny BernsteinŌĆÖs 61 round-wins, set in 2001; he needs just 14 round-wins in the last eight events to do it before yearŌĆÖs end. Also in sight is Larry DixonŌĆÖs 2002 record of 14 final-round appearances -- Schumacher needs just four more money-round showings to break that mark ŌĆō and with a win in Reading, he would tie his own class record of five straight victories, set in 2005.

Amazing also is that Schumacher and Dixon each began the year with 41 victories; as Schumacher noted after his Brainerd win, ŌĆ£When we started the season, JoeŌĆÖs record seemed so far away. Fast-forward 16 races, and weŌĆÖre knocking on the door.ŌĆØ

When he opens it, will he be greeted as the greatest ever?

|

I wasnŌĆÖt around to chronicle some of the sportŌĆÖs great seasons ŌĆō Prudhomme notching six wins in eight starts in 1975 and seven of eight in ŌĆÖ76 or╠²Bob GliddenŌĆÖs one-year/two-season unbeaten streak ŌĆō but I did witness John ForceŌĆÖs 13-victory season in 1996 and Greg AndersonŌĆÖs 15-win domination in 2004, and itŌĆÖs interesting to watch the reaction of both the fans and the media to domination.

When Prudhomme was on a tear, he was the king; when Anderson was doing likewise, fans were demanding the car be torn down looking for illegalities. When Force won nine of 10 championships in the 1990s, he was a god to the fans; when Bernstein dominated the Funny Car championship for four years in the late 1980s, fans made up Bernstein Buster T-shirts. It appears that, for whatever reason, one eraŌĆÖs dominance is another eraŌĆÖs nuisance. Go figure.

There hasnŌĆÖt been a backlash against SchumacherŌĆÖs rout ŌĆō he won the Western Swing, is undefeated at the 1,000-foot distance, and has a 16-round win streak going (five shy of his own record, which╠²spanned the╠²2005 and 2006 season) ŌĆō or his multiple championships, but will it some day be regarded with the same reverence as the accomplishments of Prudhomme or Glidden?

I think╠²the absence of backlash╠²is at least partially╠²credited to crew chief JohnsonŌĆÖs high regard among the fans, which began with his and brother BlaineŌĆÖs dominance of the Top Alcohol Dragster ranks and their near ascension to the Top Fuel throne in 1996, and to the team's uncanny ability to reach down and gut out tough performances, as best evidenced by 2006's "The Run."

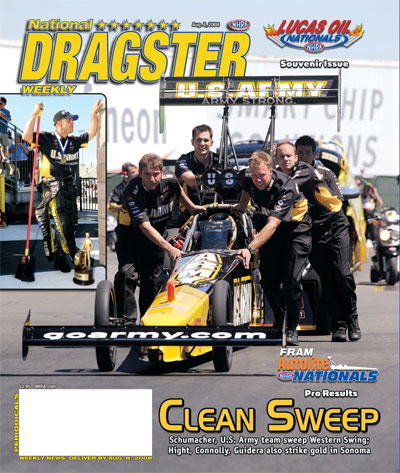

Schumacher, certainly, does his part, remaining respectfully humble of his accolades and publicly appreciative of the contributions of his entire team ŌĆō he was thrilled that we chose to feature the team on the Sonoma cover (pictured at right) ŌĆō and IŌĆÖve not seen any Demote the Sarge shirts.

Best ever?

Only time will tell.

|

After each national event, I look forward to chatting with former Top Fuel and Funny Car winner Mike Dunn, now serving as color commentator for ESPN2ŌĆÖs coverage of the 91░Ą═° POWERade Series. After going over his thoughts for his Final Take column for National DRAGSTER, Mike and I will usually chat about any number of things, from his bicycle riding to his sonŌĆÖs baseball practice to funny behind-the-scenes tales from the broadcast booth, but this week, I wanted to know how he felt about the inclusion in our current poll of the Joe Pisano Olds Funny Car that he powered through the 270- and 280-mph barriers in the late 1980s.

ŌĆ£That was a great car,ŌĆØ he answered without hesitation. ŌĆ£I still get people telling me how much they loved it, and it was my favorite car to drive, without a doubt, for a couple of reasons.

ŌĆ£First, it was fun to drive. We still had the two-speed transmission, and we had a manual lockup, so I had a lot to do as the driver. We had a line-loc button on the brake handle so that if it smoked the tires on the dry hop, I could set the brake pressure to stay on a little as it left the line. At 100 feet, IŌĆÖd push a button to lock up the clutch and push it again to lock it up again at 400 feet -- it was just an old L&T clutch that would move forward and slam in the levers ŌĆō and I would run low gear until 1,000 feet, unless it nosed over, in which case IŌĆÖd shift it early. We didnŌĆÖt even have an air shifter ŌĆō just the handle between your legs you had to yank back. When I put it in high gear, it would really set me back in the seat; it was really flying. Joe ran it lean, but with a lot of nitro. ThatŌĆÖs how we ran the big speed.

ŌĆ£We ran it like it was high gear,ŌĆØ he explained. ŌĆ£I didnŌĆÖt really know what I was doing at the time. I just hung a bunch of weight on it. Leonard Hughes came by one time and saw our pressure plate and told me there was no way we could run that much weight; he was convinced that I was screwing with everyone.

ŌĆ£Plus Joe used to love the fact that we didnŌĆÖt have a computer -- it was cool, kind of an ego thing to say we ran good without a computer -- ╠²but IŌĆÖm telling you there were times it killed us.

|

ŌĆ£I remember one year in Englishtown and the car just wasnŌĆÖt leaving hard. Joe kept telling me the clutch was messed up, which was a standard thing for him to say; it was either the clutch or the driver that was messed up, and both times that meant me.

ŌĆ£I kept putting weight on the clutch to get the car to move, but I got to the point where it was slowing down even more, so I knew something was wrong somewhere else, but Joe kept telling me the motor was fine. On the last run, I hit the throttle, and there was nothing there, so I lifted. Joe said, ŌĆśIt must be your clutch.ŌĆÖ So I pulled the clutch out and couldnŌĆÖt find anything wrong with it, so he said, 'It must be the transmission,' so I pulled the transmission out, and itŌĆÖs fine. So he said, ŌĆśWell, it must have broken the rear end,ŌĆÖ and even though I knew that wasnŌĆÖt it, I checked it anyway. It was fine. Finally, we checked the engine, and all of the pistons were burned. Both fuel pumps were junk! They must have been going away for a lot of runs, but because we didnŌĆÖt have a computer, we didnŌĆÖt catch it. So he puts two new pumps on there, and I yanked a bunch of weight back off the clutch, and first round, it blows the tires off at the hit of the throttle because we had no idea where we needed to be.ŌĆØ

See, Mike, it was the clutch ŌĆ”

ŌĆ£The other reason I loved that car is because it changed my career,ŌĆØ he added. ŌĆ£My career was going into the tank at that time. I drove RolandŌĆÖs [Leong] car until the end of 1984, and the only thing I was known for was being upside down and on fire, so I really didnŌĆÖt have much of a reputation in that car. Joe and Gene Mooneyham helped me get the deal driving [Greg ArtzŌĆÖs] Nighthawk car ŌĆō but we only ran match races and then the last two national events of 1985 -- we qualified at Phoenix but not Pomona -- and then I picked up the ride with Pisano in ŌĆÖ86, and it really established me as a driver and a clutch guy, even though we only ran a handful of national events each year.

ŌĆ£One of the greatest compliments I ever heard about the car was Austin Coil saying he was just glad we didnŌĆÖt run all of the national events.

"Man, that car was something else.ŌĆØ